Effective risk management is partly about being aware what has a high probability of working and when. One of the lessons of the Credit Crunch for many in hedge fund land is that there are market circumstances in which the previously assumed risk controls will not work. That is, the manager has a series of limits and stops and processes which in combination will produce the desired outcomes for most market conditions. The rub, as revealed in 2008-9, is in the conditional "most". Managers have to be aware of in what market circumstances their approach to markets will not work.

For most equity long/short managers most of the time the key decision variables at the portfolio level are about managing the net exposures to market, and specifically about managing the net beta-adjusted exposure to the market. There is a sub-set of equity managers for whom this is not true - those which have a limit on their net exposure to markets, and are structurally close to net neutral, say a band of 0-20% net long. Often the latter funds are quantitatively-driven equity long/short funds, but some discretionary managers choose to be close to net neutral. For these net-constrained funds returns have to come from stock selection to a much greater extent than funds with wider investment powers. The corollary is often a larger gross exposure to markets - consistent with the formulation of information ratios of managers. Typically, funds with a small net exposure limit target lower absolute returns, and implicitly rank risk-adjusted returns as a higher goal than absolute returns.

The majority of managers in equity long/short try to use the additional degrees of freedom they have in balance sheet disposition to produce higher absolute returns (than a net-neutral manager) though nearly always with higher volatility of returns. The tactical shape of the fund should be a function of two things: the market regime and the opportunity set for the particular investment style of the manager. There is a considerable range of understanding amongst managers of the necessity of taking these two dimensions into account in setting the net exposure of equity hedge funds. The best managers are good at both, but the majority of equity hedge fund managers are not. Yes, the majority.

The successful shaping of the hedge fund balance sheet requires two attributes in the manager: an ability to read the market regime in multi-dimensions, and a high degree of self knowledge about the applicability (and effectiveness) of their investment processes. Around the time of the Tech Bubble the first required ability was demonstrated a lot by equity hedge fund managers. The monetary stimulus provided by Greenspan on fears of the Millennium bug was read by managers as a bull market condition green light, and most managers were very net long in 1999, and investors were gorged on the excellent returns produced. The reverse happened from March 2000 onwards. By the 3Q 2000 many equity hedge funds were net short on a tactical basis, i.e . the managers jobbed from the short side. From 2003 to mid 2008 a net long bias and a buy-the-dips mentality were positive attributes for managers. Over the same period many new hedge fund managers joined the industry, and several big names closed down, citing the lack of shorting opportunities as a reason.

So coming into the Credit Crunch phase of 2008 only a minority of equity hedge fund managers expressed an ability to read the market regime by going net neutral or net short. A majority of managers had never been net short to that point, and many did not have that available as a choice because of their offering memoranda, or because the operational limits they gave themselves precluded it.

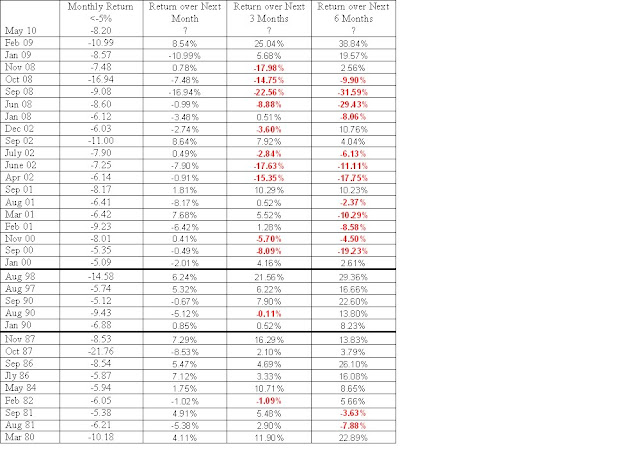

Current market conditions have echoes of 2008-9: large daily declines in equity prices, volatility and rising fear gauges in the price of gold and the cost of interbank borrowing. These are difficult conditions in which to manage an equity hedge fund. Quite how difficult is in part reflected in today's chart of the day. Every manager can tell you about the level of market volatility reflected in the Vix Index. This captures the current level of volatility in the market on a traded basis. The actual volatility experienced in the market is lower than the traded level, though intra-day measured volatility can be higher than that indicated by the Vix.

All equity hedge fund managers are aware of how volatility shifts impact their style because they can see it in the daily P&L changes per position, and the same at the portfolio level, and they are aware of the Vix. Those managers who take risk measurement more seriously will be aware of the Value-at-Risk of their portfolios. The same portfolio will have a different measured risk dependent on market conditions - when markets are more volatile measured risk goes up for the same portfolio. What is less well explored is the other element that feeds into the risk measure VaR, that of correlation.

The inter-relatedness of positions has an impact on measured risk. The more related the positions the less diversification there is in a portfolio. Consequently managers structurally build diversification into their portfolios by having limits on sectors/industries/macro-related themes as well as limits to specific stock risk by constraining holding size. But correlation is not stable. Cross-sectional correlation varies through time. In up-trending markets (scenario 1) volatility drops and stocks tend to become less correlated. For sideways moving markets (scenario 2) two stocks in the same sector could quite feasibly act differently - one going up and the other staying the same price, or even falling. Scenario 1 is better for producing returns from net market exposure, and scenario 2 is a richer market opportunity for returns purely from idiosyncratic stock risk (selection).

However when markets fall for a period volatility rises and correlation increases. The correlation coefficients of stocks' betas go up - the market component of stock price changes goes up, and the sector effect increases and the idiosyncratic component of stock price changes declines. The chart of the day below illustrates that we are at an extreme for measured correlation amongst S&P500 constituents.

In such a market environment portfolio returns become a product of the net market exposure, driven by the weighted average of the portfolio betas. The extreme case illustrates the point - bank shares and commodity stocks have had the highest betas in the market for some years now. The return to the net exposure to these two sectors plausibly could have been the largest component of the return of individual equity hedge funds over the last three years. For net neutral equity hedge funds the net exposure decision on these two sectors over the last three years could have even been the decision that determined return outcomes.

Given that nowadays few managers can demonstrate an ability to read the market regime in multi-dimensions, and have a high degree of self knowledge about the applicability of their investment processes, I expect negative returns from the strategy for the current market. What is particularly disappointing is that the number of managers who can show they truly learned lessons from 2008-9, and can make money now, are so few. Maybe investors have to exhort their managers to take some off some of the net exposure restrictions - or do investors doubt that their managers have sufficient skills to handle wider investment powers?